What do historians do over spring break? Dr. Elizabeth Penry, Associate Chair for Undergraduate Studies, traveled to Argentina for research and sent us this postcard from Buenos Aires.

With the support of a generous Faculty Research Grant from Fordham University, I have begun work on a new project on indigenous literacy practices in the colonial Andes (16th – 18th centuries). Over the spring break, I traveled to Buenos Aires to work in the Archivo General de la Nación. The geographic focus of my work is that region of the Andes that became the modern nation of Bolivia. Part of the Inca empire at the time of the Spanish invasion, it formed the southern region of the Viceroyalty of Peru for over 200 years until it was incorporated into the new Viceroyalty of the Rio de la Plata, headquartered in Buenos Aires, at the end of the 18th century.

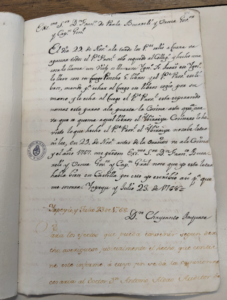

A 1768 Complaint about Book Burning

Finding information about indigenous literacy is a little like hunting for a needle in a haystack; there isn’t any division in any colonial archive dedicated to the topic. But in addition to 250 years of detailed records of royal orders, the Argentine national archives are particularly rich with census and economic records for the region, and sometimes surprising information turns up. Orders coming from Spain demanded that schools be established in every indigenous town and that native Andeans should learn Spanish, but they rarely provided monetary support. However, I found tax records that list funds paid for indigenous village school teachers. Even more interesting is how many indigenous people were labeled ‘indios ladinos’ the term Spaniards used for natives who were fluent in Spanish language and culture. Indios ladinos were identified as town criers, translators, church sacristans, and frequently were responsible for writing legal petitions for their communities. In one unusual case that I found, an indio ladino accused a priest of being complicit in the burning of books. Although he claimed not know the titles of the destroyed books, this native Andean was horrified by the sight and filed a complaint with officials. All these small details will allow me to create a detailed composite picture of indigenous practices related to literacy in the colonial period.

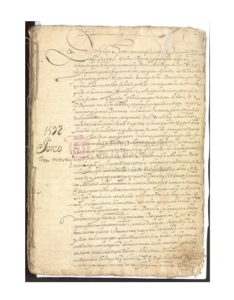

A 1592 order for a new census following a measles epidemic

A 1611 Census Report

Besides archival work, I met with colleagues at the Universidad de Buenos Aires. The university has a very active program in Andean history and it was great to compare research notes with fellow scholars. Argentine colleagues made my research much easier by sharing their detailed knowledge, as well as catalog records of local archives. Of course, just being in Buenos Aires is wonderful. One of the wealthiest countries in the world at the turn of the 20th century, Argentina, like the US, is a nation of immigrants. In particular, large numbers of Italians (like the family of Pope Francis) came to Buenos Aires, influencing the cuisine and the language. After a day of archival research, it’s hard to choose between a parrillada (grilled meats) or ñoquis (gnocchis) prepared Roman style to go with un buen Malbec. One of the great joys of working on the colonial Andes is the opportunity to work in archives in many different countries, and to have colleagues literally around the globe.

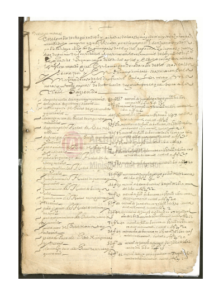

Entrance to Archivo General de la Nación in Beunos Aires