In another in our continuing series of “Postcards,” Dr. Elizabeth Penry sends news from her research in Rome.

In early June I traveled to Rome to conduct research in the Jesuit archives, the Archivum Romanum Societatis Iesu (ARSI). With the generous support of a Faculty Research Grant from Fordham University, I am doing preliminary research on a new project on indigenous literacy in the colonial Andes (16th-18thcenturies).

The reading room in the Jesuit archives in Rome

Founded in 1545, the Society of Jesus became known in the early modern world for educating elite sons of society. What is not as well known is that Jesuits fathers operated schools for indigenous peoples in the Americas from the late sixteenth century until the suppression of their order in the eighteenth century. In the Viceroyalty of Peru (a vast area that incorporated all of Spanish South America in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries), the Jesuits manned the important indigenous parish of Juli on Lake Titicaca for nearly two hundred years, and extensive missions in the eastern part of the viceroyalty that later became Paraguay. In both places Jesuits operated printing presses and grammar schools for commoner Indians. Jesuits also operated schools for elite native Andeans, sons of native hereditary lords, in the key cities of Cuzco, Potosí, and Lima. The ARSI in Rome has extensive holdings on the mission fields in Peru, including letters describing how and what pupils were taught, and how the schools were funded.

A view of St. Peter’s on my morning walk to the archive

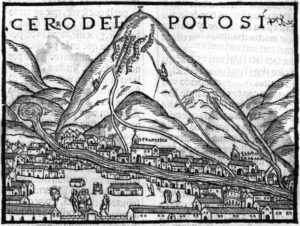

While working at the ARSI, I found evidence of an indigenous woman’s financial contribution to the Jesuit school in Potosí (in modern Bolivia). In the late 16thcentury, Ana Parpa, a literate indigenous woman, wrote a will leaving over 22,000 pesos to the Jesuits to be used to fund their school for educating elite indigenous men. This was quite a large fortune, roughly the equivalent of $300,000 today. Ana Parpa lived in Potosí, the site of the largest silver strike in the world and the first region of large scale capitalist production. Silver pesos (the famous ‘pieces of eight’) issued by the Royal Mint in Potosí beginning in 1574 quickly became a world-wide currency because of their consistent weight, used not only in the Americas, but also in Europe and Asia. In the 1590s when Ana wrote her will, Potosí was one of the largest cities in the world, rivaling Paris or London. It’s not clear where Ana Parpa’s great wealth came from, but it seems likely that Ana invested in mining. Because she had no family, Spanish law allowed her to bequeath her wealth in any way she saw fit (if she had a husband or children, the law would require that she leave a portion to them). Although the will contains formulaic language, it is clear that Ana believed that the Jesuits were doing “good works” in Potosí. The will also provided that Ana would be buried in the main chapel of the school and that masses would be sung for the repose of her soul. Although a relatively small number were educated in the Jesuit schools, the schools were influential.

The bequest of Ana Parpa complicates the popular understanding of the relationship between indigenous people and Spaniards and of indigenous attitudes towards Christianity. This set of documents from the ARSI also shines a new light on how indigenous schools were funded and the value placed on them within colonial society.

Cieza de Leon’s 1553 map of Potosi