Sven Beckert’s Empire of Cotton is about how cotton became the key commodity in the making of nineteenth-century global capitalism. It’s the story of land and slavery, financiers and merchants, and competition between the American South and India for dominance in production. But Beckert hesitates to define capital or capitalism. Here is a quick take and a few thoughts about the word itself and the world it creates.

Capital is money in motion. It’s not a bag of seed or a college education or an idea for a new business or your terrific potential as an artist or the car you drive to work. It’s not even the same thing as wealth. If capital is any of these things, then it’s existed for as long as Homo sapiens and has no historical specificity. It is surplus value in the act of generating surplus value–profit that creates profit. Marx expressed it as M→C (LP + MP)→P→C’→M+∆M, in which Money is advanced to buy Commodities, consisting of Labor-Power, the Means of Production (which would include land or factories and raw material). Labor is the most important purchase because it is the only factor that creates more value than it costs. If a capitalist pays someone $10 for a day’s work he can use their labor-power to manufacture $100 in widgets. Labor combined with the means of production results in second-order Commodities. These must be sold for the original Money advanced, plus an increment (the surplus-value). Money does not become capital until or unless it is advanced. To paraphrase Forest Gump, capital is as capital does.[i]

The word first appeared between the twelfth and thirteenth centuries for the top or head of something (from caput, or head), like the Corinthian capital of a marble column. It referred to the greatest height or degree, like a capital crime, a capital enemy, capital wounds, and a seat of government (all between 1400 and 1600). At the same time capital developed toward an important sum of money. Fernand Braudel found this sense of the word in Italian as far back as 1211. St. Bernardino of Siena wrote in the late fourteenth or early fifteenth century of “that prolific cause of wealth we commonly call capital.” But sums of money had not yet become perpetuating funds.

Other English words carried similar meanings. Cattle and chattel came into English between the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, not as words for barnyard creatures but for property, goods, and even money itself. Horses, oxen, and bovines became cattle (around 1400) because they were significant property. The word did not refer to animals as animals in the fifteenth century and did not refer specifically to bovines until the sixteenth century. Stock, another word for accumulated value, stood for something that sprouted and spawned endlessly like a stem or tree trunk until about 1380 when it shows up as a word for domesticated animals. It did not describe a growing herd of livestock until the sixteenth century. But once it did, around that time, stock took a turn. It began to take on meanings similar to capital. It 1526 it referred to money that could be invested, and by 1714 the word was in common use as the subscribed capital of a merchant house.

Capital pulled away from these other words. By the time Smith published The Wealth of Nations political economists in Britain and France had already given capital the meaning it carries today. Smith used the term “capital stock,” suggesting money that reproduced a percentage of itself in a given time. According to Braudel a Russian consul made the essential distinction, reporting that France under Napoleon Bonaparte fought “with her capital,” while the countries that France invaded fought “with their income.” For centuries few institutional pathways existed for employing income in order to earn income. Capital appeared along with these pathways, as people needed a word to differentiate this new entity from merchant wealth and the dividends represented by lambs and calves.[ii]

Historians ask all sorts of questions about capital. One of them is who is inside and who outside its creation. If the owner of one of a sandwich shop on 9th Avenue in New York City reinvests some of her profit by buying bread and tomatoes or by making improvements to the kitchen does that make her a capitalist? What if she has a retirement account with a brokerage firm? Is she a capitalist for making a living in a society organized by capital? To think so blurs categories. It equates the owner of a bodega to the owners of Standard Oil. Firms that generate vast capital have certain characteristics. They tend to operate across national boundaries. They diversify their investments, so that they do not commit themselves to any one commodity. They have deep ties to governments and the global political economy that includes international banking. And they are always looking for new places to get hold of resources and hire labor. There are certainly small capitalist firms, and a business like Wal-Mart began as a country store in an Arkansas town. Capitalism comes from the larger social order, but it then seeks to dominate it. That does not describe the owner of the sandwich shop.

On second thought, maybe we are all capitalists in certain sense. Whether we generate capital or not, command it or not, manage it or not, capital has brought almost all of our occupations into existence. Occupations shape identities, situating people within institutions that lend internal coherence to the social system, regardless of its contradictions. And that social system is tightly bound up with the United States, so much so that many patriotic Americans make little or any distinction between the freedoms detailed in the Bill of Rights and “free enterprise,” even though entrepreneurship has existed for as long as people bought and sold things and even though capitalism in the eighteenth century is nothing like what it is today. “The worst error of all,” Braudel reminds us, “is to suppose that capitalism is simply an ‘economic system’, whereas in fact it lives off the social order, standing almost on a footing with the state, whether as adversary or accomplice.”

So complete has capital become throughout the social order that it appears to have emerged from the natural order, and the behavior it instills seems to many people to be an expression of universal human motives and aspirations. As three historians observe, “One of the distinguishing features of a free-enterprise economy is that its coercion is veiled … Far from being natural, the cues for market participation are given through complicated social codes. Indeed, the illusion that compliance in the dominant economic system is voluntary is itself an amazing cultural artifact.”[iii] It might be true that the gentry did the same thing in 1650 that they did in 1250. They extracted value from people and environments. But they did it differently than anyone had before, through a discipline imposed by rents and wages, through social codes and cues that appeared to be independent of people. They aren’t. Perhaps the most radical idea we can have about capital, the single most subversive thing we can think about it, is that it begins as nothing more than a relationship between people. Like the meanings of words, relationships change.

[i] “I should say that this is the circuit of capital. It is not a formula for capitalism, which is an entire social system that is based on the recreation or reproduction of capital. Once people began to produce capital they became committed to it, created institutions to further it, connected their identities to it, or could no longer what life was like before it. Capital found its way into so many facets of life and became the basis of giant amalgams of people and production, not to mention nation-states, that any substantial change now seems like it would amount to the end of the world.” – Marx, Capital, Volume 1, 247.

[ii] Fernand Braudel, Wheels of Commerce, tr. Sian Reynolds (New York, 1982), 232-234; Oxford English Dictionary; Smith, Wealth of Nations, 353-355.

[iii] Joyce Appleby, Lynn Hunt, and Margaret Jacob, Telling the Truth About History (New York, 1994), 120-1.

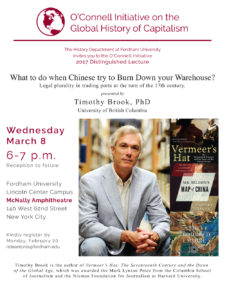

On the evening of Thursday, March 8th, the History Department opened its O’Connell Initiative Annual Conference titled “The United States and Global Capitalism in the Twentieth Century” with Dr. Vanessa Ogle as it’s keynote speaker. Dr. Ogle is a professor of History at University of California-Berkeley with a focus on late-modern Europe. Faculty, graduate and undergraduate students alike filled the McNally Amplitheatre to hear Dr. Ogle’s talk, titled “Twilight Capitalists: The Global Cold War and the Unmaking of Post-War Colonialism”.

On the evening of Thursday, March 8th, the History Department opened its O’Connell Initiative Annual Conference titled “The United States and Global Capitalism in the Twentieth Century” with Dr. Vanessa Ogle as it’s keynote speaker. Dr. Ogle is a professor of History at University of California-Berkeley with a focus on late-modern Europe. Faculty, graduate and undergraduate students alike filled the McNally Amplitheatre to hear Dr. Ogle’s talk, titled “Twilight Capitalists: The Global Cold War and the Unmaking of Post-War Colonialism”.